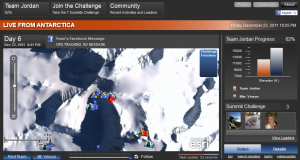

Our team just finished a massive 5 weeks push to building an app for the Romero family, and in particular Jordan, to follow him on his climb of the final summit on the continent at the bottom of the world. You can find the app on his home page today https://jordanromero.com, or access it directly here https://edn1.esri.com/antarctica.

It was actually Jordan’s dream to climb the highest summits on the major continents. And, he is now on his way to accomplish all that…and before his 16th birthday during what is considered summer in Antarctica. I’m amazed at what he has done. I can’t help but think about what he might be able to accomplish in the future now that he has accomplished a feat that very few ever do.

The app is capturing live GPS coordinates (altitude, heading, speed, lat/lon), live weather and it also includes a Challenge component that anyone can take to conquer their own 7 summits on their own time by walking, swimming, running or biking.

I encourage you to check out the app and even take the Challenge!

For the techno-geeks reading this, here is some background info on the technology. GPS processing and ArcGIS mapping backend services were built in C#.NET by AL Laframboise. The Challenge service and REST endpoints were built in C#.NET by Nick Furness. I built the the Adobe Flex/ActionScript client application using Adobe FlashBuilder 4.5, and the ArcGIS API for Flex provided the client-side mapping. The look and feel were accomplished by the excellent help of UX engineer Frank Garofalo in Esri Professional Services. The client app uses a custom dependency injection model at the core, and the skins were built using Adobe Catalyst.