This blog post builds on concepts proposed in an earlier post about not all mobile apps being created equally. If you are a developer who is in the process of migrating to mobile this post is for you. It’s intended to raise awareness of important items to consider in your requirements. My goal is to help you identify some of the major gotchas early on in the development process and improve your chances for success.

There are many more details to learn on the topics I’ve described below. The good news is that in the last few years the amount of deeply helpful documentation has expanded considerably. Where possible I’ve tried to include links related to each topic.

Touch-based Workflows. Recent research has shown that people use their smartphones more often than web apps, and they spend roughly 80% of their time on social media and games. Because of this and the fact that smartphones today are touch driven and not mouse driven, you have to take that into account in your user interface design. Touch implies many things including gestures and multi-touch. You can toss your old conceptions of user interface design based on desktops and tablets, and check out Android’s recommendations as well as Apple’s. My strong recommendation is to hire a UX designer to help you through building a user interface.

Mutliple form factors come with various screen sizes and densities. Long gone are the days of building for just three main browser types. Now you have to take into consideration iPhones, iPads, tablets, numerous different style androids as well as desktop and laptops. Android defines the following screen sizes and, as you can see, this is quite varied and smaller than a typical laptop or desktop. Those typically run 1024 x 768 or greater.

- xlarge screens are at least 960dp x 720dp

- large screens are at least 640dp x 480dp

- normal screens are at least 470dp x 320dp

- small screens are at least 426dp x 320dp

This is important to know because an app that looks good on an iPad may not look good, or display correctly, on the four inch display of a Motorola Atrix at 960 x 540. A button that looks correctly sized on one smartphone may look too big on another. A whopping 84% of all Android screens are what Android defines as normal size (>= 470dp x 320dp) and between either medium dpi (~160dpi) or high dpi (~240dpi). But, you still have to take into consideration other densities. I also recommend taking a look at new HTML5 browser-based technologies to help with addressing this problem, such as CSS media queries.

Inconsistent Internet. It’s a best practice to check if internet connections exist and gracefully handle HTTP requests when the internet is down, as I blogged about here. Depending on your application and needs, you should also monitor whether or not a wireless connection can be made and then allow the application to switch to wireless where possible. Wireless also has the advantage of using less battery power.

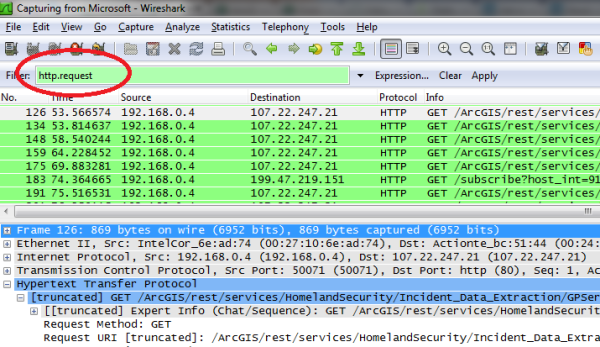

Slower Connections. And, on a related note, you can’t always depend on 4G connections having consistent maximum download speeds. Over the course of a user session, the connection speed will vary widely and you should plan for that. I’ve been trying to find some stats on mobile internet quality world-wide, if they are out there they are hard to find. But, we’ve all experience spotty mobile internet coverage. Take this into account if you are transferring large amounts of data between your servers and your app. You should also consider detecting when the user is in an area of greater bandwidth and use that to download more data less often. Use loosely coupled and event driven architectures. Test app load times on various devices and around town and away from your office.

Less CPU Horsepower. While the latest generation of four core phones are certainly the most powerful phones yet. In general, applications and web pages will run slower on phones than they do on your development machine running a desktop browser. Take older generation phones into account because they are usually significantly slower than the newer phones. There are a few workarounds in HTML5 to help with this, in that done correctly they can offload rendering to the hardware. In native applications be aware of memory leaks because, remember, more memory usage means less battery life and applications that can run slower over time.

Support across multiple operating system versions. Remember on Android that the vast majority of users are still running v2.2 – v2.3.7 even though v4.x is currently shipping. You’ll have to do some research on your target market and find out what versions and type of phones they are using. You can’t support everything, but you can make educated guesses. Apple, on the other hand, has a significantly more limited selection of phones and tablets that you have to support, and they do a great job helping you support those.

There are some solutions that help with building cross-platform mobile apps, to go into more detail will take another blog post. Here’s a few: Adobe Flex, PhoneGap and Titanium. Keep in mind that the future of Flex, as a development platform, is being called into question after Adobe open sourced everything but the browser and desktop runtimes to the Apache Foundation. PhoneGap and Titanium offer what is now being called “hybrid” solutions where you can build an application in JavaScript, for example, and then compile that code for native deployments on Android and iOS.

Battery Life. Ah, battery life is last but certainly not least. Be aware of how battery intensive your application is and try to minimize battery consumption as much as possible. The Android online docs have a number of highly information articles on this subject. Smaller app footprint in memory means less battery consumption. Heavy CPU usage means more battery usage. Minimize GPS usage through smart algorithms to help preserve battery life. Switch to 802.11 wireless connections where possible, since this requires less battery power than 3G and significantly less power than 4G.

So, there you go. I hope these suggestions help. If you have more suggestions based on your own experience please post a comment!

References:

Android Screen Sizes and Densities