This post takes a closer look at Base64 image performance, offers some use cases and raises some questions. I’ve had a number of conversations recently over the benefits of using client-side, Base64 image strings to improve web app performance over making multiple <img> requests. So I ran a few tests of my own, and the results are shown at the bottom of the post.

If you aren’t familiar with them, a Base64 image is a picture file, such as a PNG, whose binary content has been translated into an ASCII String. And, once you have that string then copy-and-paste into your JavaScript code. Here’s an example of what that looks like:

<html>

<body onload="onload()">

<img id="test"/>

<script type="text/javascript">

var html5BadgeBase64 = "iVBORw0KGgoAAAANSUhEUgAAAEAAAABACAYAAACqaXH…";

function onload(){

var image = document.getElementById("test");

image.src = "data:image/png;base64," + html5BadgeBase64;

}

</script>

</body>

</html>

There are other ways of doing this that I’m not covering in this post such as using server-side code to convert images on the fly, passing Base64 strings in URLs, etc.

The most commonly cited advantage is that including a Base64 string in your JavaScript code will save you one round-trip HTTP request. There is absolutely no argument on this subject. The real questions in my mind are: what are the optimal number and size for Base64 images? And, is there a way to quantify how much if any they help with performance?

Size? Base64 image strings will always be larger than their native counterparts. Take the following example using a copy of the relatively small HTML5 logo and a decent sized screenshot. As you can see the text equivalent is 33% and 31% greater, respectively.

Html5.png = 1.27KB (64×64 pixels)

Html5base64.txt = 1.69KB (1738 characters)

% Difference = +33%

Screenshot.png = 19KB (503×386 pixels 24bit)

ScreenshotBase64.txt = 24.9KB (25584 characters)

% Difference = +31%

In comparison, when working with <img> tags you’ll be working with an ID that points to the actual image file stored in memory.

Convenience? As you can see, the length of your base64 strings can get quite long. The simple HTML5 logo in the previous example becomes a 1738 character long string and that’s only 1.69KBs worth of image.

Can you imagine having a dozen of images similar in size to the 19KB Screenshot example? That would create over 300,000 ASCII characters. Let’s put that into the perspective of a Word document. Using 1” margins all the way around, this would create a document approximately seven and a quarter pages long!

I assert that Base64 is best for static images, ones that don’t change much at all over time. The bigger the image the more time consuming it can become convert it, copy-and-paste it into your code and then test it. Any time you make a change to the image you’ll have to repeat the same steps. If you accidentally inject a typo into a Base64 string you have to reconvert the image. That’s simply the best approach from a productivity perspective.

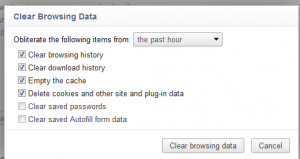

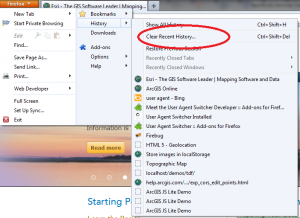

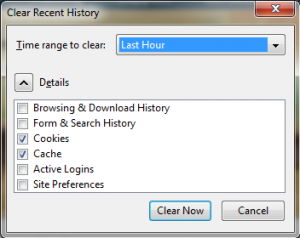

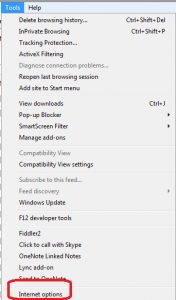

In comparison when using a regular old PNG file, you create the new version, copy it out on the web server, flush your browser cache, run a quick test with no need to change any code and bang you’re ready to go have a cup of coffee.

Caching? It depends on your header caching settings, browser settings and web server settings. I’ll just say that typically base64 images will be cached either in your main HTML file or in a separate JavaScript library.

Bandwidth? Using base64 images will increase the amount of bandwidth used by your website. Compare the size of your HTML file with Base64 images to the size of the same file simply using <img> tags. You can do some basic math if you add up the size of a particular page and multiple it by the number of visits. Better to err on the side of caution, because there really isn’t a good way to tell which images and JavaScript files are getting catched in your visitors browsers and for how often. Here’s an example where you have a 30GB bandwidth limit per month, and simply converted all of your PNG images to Base64 could very easily push you over the limit:

100,000 page hits/ month (main.html) x 256KB = 25.6 GB (incls. 75KB of standard PNG images)

100,000 page hits/month (main.html) x 293.5KB = 29.4 GB (incls. 97.5KB Base64 images)

Also, some providers give you decent tools that you can use to experiment with Base64 images versus regular images and test that against your bandwidth consumption.

Latency? This variable doesn’t really apply directly to Base64 images. There are many factors that determine latency that I’m not going to discuss here. There are some more advanced networking tools that let you figure out average latency on your own web servers. Every request will be unique based on network speed, the number of hops between the client and the web server, how the HTTP request was routed over the internet, TCP traffic over the various hops, load on the web server, etc.

A few quick performance tests.

What would a Base64 blog post be without a few tests? I devised four simple tests. One in which I referenced a JavaScript file containing Base64 images. One which contained five <img> tags and then I re-ran the tests again to view the cached performance.

These tests were performed on a Chrome Browser over a CenturyLink DSL with a download speed of 9.23MB/sec and an upload speed of 0.68MB/sec. Several tracert(s) of TCP requests from my machine to the web server showed more than 30 hops with no significant delays or reroutes. The web server is a hosted machine.

Test 1 – JavaScript file with Base64 images.This test consists of an uncached basic HTML file that references a 125KB JavaScript library containing five base64 images.

Time to load 1.9KB HTML file: 455ms

Time to load 125KB JavaScript file: 1.14s

Total load time: 1.64s

Test 2 – Cached JavaScript file with Base64 images. This test consists of reloading Test 1 in the browser

Time to load cached HTML file: 293ms

Time to load cached JavaScript file: 132ms

Total load time: 460ms

Test 3 – using <img> tags to request PNG images. This test consists of an uncached HTML file that contains five <img> tags pointing to five remotely hosted 20KB PNG files.

Time to load 1KB HTML file: 304ms:

Time to load five images: 776 ms

Total load time: 1.08s

Test 4 – cached html file using <img> tags to request PNG images. This consists of reloading Test 3 in the browser

Time to load cached HTML file: 281ms

Time to load five cached images: 16ms

Total load time: 297ms

Conclusions

It’s not 100.0000% true that multiple HTTP requests results in slower application performance in comparison to embedding Base64 images. In fact, I’ve seen anecdotal evidence of this before on production apps, so it was fun to do a some quick testing even if my tests were not completely conclusive beyond a doubt.

My goal was to spark conversation and brainstorm on ideas. I know some of you will say that thousands of tests need to be run an statistically analyzed. My argument is that these tests represented actual results that I could see with my own eyes rather than being lumped into some average or medium statistic.

Note that I’m just posting a snapshot of the tests I ran. I didn’t have enough time to draw up a significant battery of tests to cover as many contingencies as possible. However, the test numbers I’ve posted were fairly consistent in the favor of the multiple PNG requests loading faster than a single .js file containing five Base64 images. Obviously more significant testing is needed to sort out other real-world variables, such as image file sizes versus application size and under a variety of conditions and different browsers.

Resources

JavaScript library with five Base64 images

HTML file that reference JavaScript library of five Base64 images

HTML file with five <img> tags

[Edited 2/26/13: fixed a few typos]